What We Can Learn from Super Metroid

Super Metroid, video game narratives, and what the children can teach us

Hello! This week I adapted an old essay of mine that I’m sure a lot of you have heard me gush about in real life. While the quality of analytical video essays on video games is slowly improving—see bearded legends Good Blood or Jacob Geller—there isn’t a place for academic writing about this still brand new art form.

Most academic discussions of video games are limited to scientific studies on the effects of playing them, or, at best, analyses on the signification in certain games’ mechanics. Most video game writing outside of academia is written by underpaid, overworked game reviewers whose job is to boil down a five to one-hundred hour experience into a number from one to ten, just so indecisive consumers will or will not spend $60. I’d like to think there’s a place for video game writing that falls somewhere in the middle of these two.

This essay, with its large paragraphs, occasionally big words, sometimes dry wording, and semiotic approach probably falls more on the side of academia. But I’m hoping to provide an example of that in-between kind of writing for video games that I don’t see enough of.

Last thing: I recently edited my About page, adding that “I don’t have much interest in specifying the purpose of this page. It’s sort of a test run.” I wanted to disclose this in a post as well. Most of my subscribers are friends and family, so this page is, for me, a comfortable environment to experiment with different forms of writing.

Once I find my niche, I will probably archive this page and start a more specific newsletter on my own. I hope you are all okay with being along for that ride, even if most of you have never played Super Metroid or any of the games I occasionally rave about here.

Video game narratives have come a long way since the 90s. In recent years I’ve played branching stories and linear masterpieces. Some of my favorite game stories have made me a marine, a Norse god, a cowboy, or a bug. Many of them have cutscenes whose acting and camerawork rival that of a film’s.

Before all this, there wasn’t much narrative to video games. Super Mario World (1991), for example, opens with a single block of text that says, “Welcome! This is Dinosaur Land. In this strange land we find that Princess Toadstool is missing again! Looks like Bowser is at it again!” That informative, yet empty text is all the story the player gets for its 96 levels. What makes the game great, though, is its level design, enemies, power-ups, and bosses. Narrative quality did not make or break a game at this time.

But Super Metroid—the third game in Nintendo’s Metroid series—raised the standards on this. The game is an action-platformer that was able to simultaneously introduce its unique and groundbreaking gameplay1 while telling a story in a particularly video-gamey way. Its unverbalized tutorials juggled between telling the player how to play and showing them what the narratives stakes were— both emotionally and literally—without you even realizing what you were being taught. As an avid speed runner of Super, only after tens—probably hundreds—of playthroughs have I gained a full understanding of the plots and themes at play. But on my first run I enjoyed it regardless, and in a much different way. Its depth allows all kinds of players to be drawn in and invested, whether they realize why or not.

I want to explore what this “video-gamey way” of telling a story is, and the familiar narrative tropes Super Metroid employs to tell a story through gameplay.

Super Metroid’s Introduction

While most video games of the 90s opened with a chipper tune and a quick display of some gameplay elements, Super Metroid starts with an incessant, rhythmic beeping, the innocent squeals of some unseen creature, and images of bloodied scientists lying dead on a laboratory floor. Eventually the frame pulls out, the music comes to a climax, and the title fades in. After this cinematic title screen, we get a full view of the scene and finally see what’s doing all that squeaking: a small green creature with a veiny look to its skin, trapped inside a capsule—a Metroid.

Fans of the series will recognize it in fear, remembering how dangerous this creature was in past adventures and how many characters wanted to steal it for their own personal gain. But newcomers might see it for what it looks likes: an adorable little alien. Paired with the infantile sounds it’s making, we might have a fondness for this Metroid larva. Its cries resemble that of a baby, invoking the player with an instinct to protect it. Using these instinctual human feelings to evoke something in the player is a large part of the Metroid series’ atmosphere, but also contributes to the thematics of its (usually) barebones narratives.

After this introduction cinematic, the player can load up the game and be introduced to our protagonist: Samus Aran. For about five screens, she monologues about her past adventures, catching up the player on what’s happened in the last two games. In this monologue, we find out that the Metroid larva from the introduction is the last living Metroid, and that in Metroid II it started following Samus around “like a confused child.”

This establishes the first motif of child and parent that we see, and specifically between mother and child—that is, if players were aware that Samus was a woman. Characterizing the Metroid as a “confused child” is the only direct characterization for anyone in the entirety of the game—mostly thanks to the fact that it is some of the only in-game text—and serves to confirm the player’s initial instinct about it during the introduction. It sets the Metroid’s position as the metaphorical child of many of the characters going forward.

After this monologue and some gameplay, we meet Ridley, who has the Metroid larva in his clutches. His giant Xenomorph-like appearance, the stabbing motions of his tail, and his kidnapping of the Metroid larva give him a masculine, phallic, and, most importantly, paternal presence. This presence (co-opted by the fact that he is the first thing in the game to damage Samus’s health) creates a parental tension between the player-character and one of the central antagonists.

After their brief battle, Ridley flies off with the Metroid larva. Samus rushes to her ship and decides to confront Ridley and the Space Pirates on her home planet, Zebes2.

In just this introduction cinematic and beginning few minutes of gameplay, Super Metroid not only teaches the player how to run, jump, and shoot, but it also introduces each of the main elements of its story: Samus, the mother; the Metroid larva, the child; and Ridley, the father. As the game progresses, more and more of these subtle father, mother, and child figures are added into the mix to help the audience subconsciously feel connected to a cast of alien characters.

Parenthood

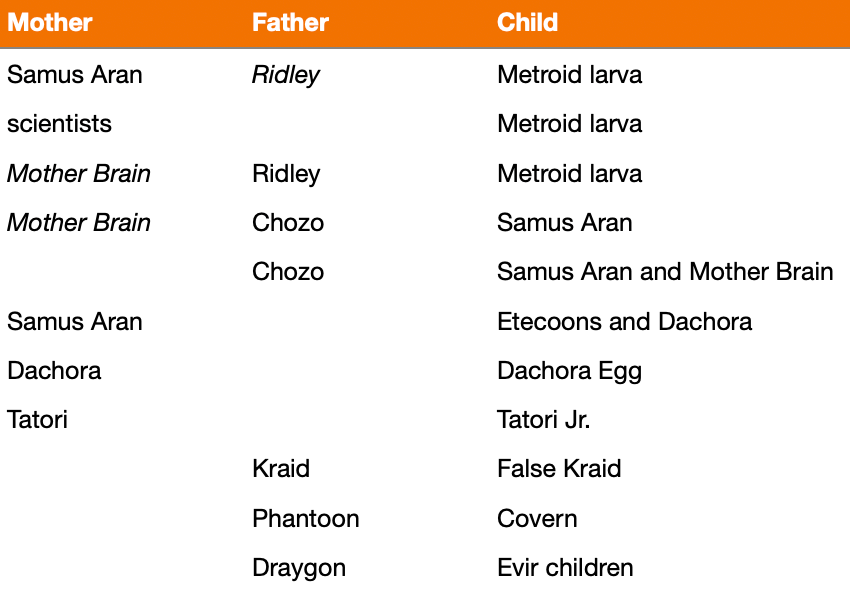

There are several examples of parent-child relationships throughout Super Metroid. These relationships are never explicitly stated and can only be inferred through visual cues, but present themselves as important foils to Samus—who is both a maternal and filial signifier.

The first of these relationships is between the Metroid larva and several characters in the game. As I explained earlier, the sole living Metroid is initially characterized as a “confused child.” The role of many of the major characters is to act as a possible parent for this child. In Samus’ monologue, we first connect her as the mother. After the battle with Ridley, we might see the Metroid as the kidnapped child of a crazed father. Later, it’s the child of the Space Pirate leader, Mother Brain—whose name makes it clear what kind of relationship she has to everyone else. In the final battle between Samus and Mother Brain, the Metroid rejects Mother Brain as its mother by saving Samus at the last moment and sacrificing itself. I’ll come back to the thematic importance of this moment later. What’s important now is that the Metroid, as the potentially powerful weapon that it is, is in a constant state of being forcibly adopted.

The second central relationship is Samus and the Chozo—an ancient race of bird-like people who once inhabited Zebes. Though other games and the manga expand on the fact that the Chozo are literally Samus’s parents, Super Metroid tells us this in a more metaphorical sense. They are never seen alive in the game, however all of Samus’s abilities come from cultural objects which have been preserved for years beneath the surface of the Chozo’s home planet. These objects often come after a test that challenges the player’s ability to fight or explore. Even after their extinction, the Chozo act as fathers to Samus by teaching her lessons and helping her grow stronger.

Finally, Mother Brain is our last example of a parent. While the Chozo represent Samus’s supportive father, Mother Brain is her abusive mother3. Mother Brain is the AI leader of the Space Pirates whose goal is to clone the Metroid in order to use its powers to rule the galaxy. Stealing Samus’s child from her, and allowing it to be experimented on and then losing it paints Mother Brain as a parent working only out of self-interest, contrasting the selfless intentions of the long-dead Chozo. They also provide a foil to Samus’s own performance as a caring mother who will stop at nothing to save her Metroid child.

Inversion of Parental Tropes

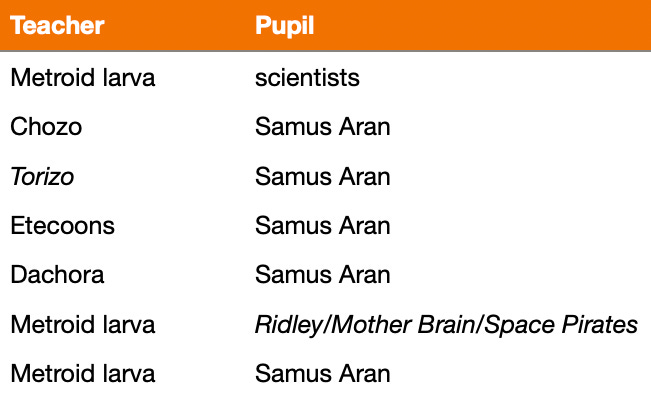

Super Metroid presents several examples of parents to nonverbally teach the player—and thus Samus—the rights and wrongs of raising a child. The connection between “parent” and “teacher” as signifiers is oftentimes inseparable. Learning and growing (as actions of a protagonist) are oftentimes encoded only to the child in a story. Super intends to subvert this code with several examples of the children doing the teaching, allowing the parents to grow.

For the majority of Super Metroid, the Chozo statues help Samus to grow stronger and use new abilities. They are initially established as the teachers. But as the game proceeds, less and less of these statues can be found. One of the statues doesn’t even offer Samus anything, and instead comes alive and battles her. Her only positive parent figure becomes distant and aggressive as the game proceeds.

So, who does Samus learn from otherwise? During a certain section near the middle of the game, the player might find themselves stuck in a vertical tunnel with three monkey-like creatures called Etecoons. They have a playful, childlike appearance to them. Because Samus cannot jump infinitely, she has no way of scaling the tunnel. With no words and no item given, the Etecoons demonstrate how to kick off a wall and jump higher. If the player carefully follows their nonverbal instructions, they can get Samus to the top of the shaft with a series of wall jumps. The Etecoons even mimic the fanfare that plays when the player picks up an item from a Chozo statue, further signifying to the audience that they are the next teachers of Samus. Super Metroid presents the sign of a helpful parent only to violate the code that it signifies, replacing the teacher with a small band of monkey kids.

The Metroid larva also serves this purpose for Samus by sacrificing itself to Mother Brain in order for Samus to live. At the start of the game, Samus throws herself into the line of fire for her child by venturing into the depths of Zebes. At the very end, the Metroid larva does the same for her by protecting Samus from Mother Brain in the final boss battle.

Oppositions and What They Conclude

There are two main kinds of oppositions happening across the cast of Super Metroid. One opposes the characters as either parent or child, illustrated here (including several examples not mentioned earlier, with enemies noted in italics):

The other kind of opposition is between teachers and learners, listed here:

Most of the “Pupil” section is populated by Samus, and for good reason: she is who the player controls. Because the player is an active participant in the story, they need to be taught certain things about how the game works, and can only improve in the game if they are taught its concepts correctly. In a movie, what the viewers interpret comes from their experiences as a person. A video game has the unique opportunity to provide the audience with experience that will color their understanding of the game’s themes and concepts.

By making the player-character the central learner of the piece, Super Metroid has a perfect opportunity to tell a story about teaching. That alone would be an interesting thematic setup—with a more meta paradigm since the learning happens between the player outside the game and the pedagogical themes within it.

But this game takes it a step further with its inversion of the function of parents. Oftentimes in society we see our parents as our teachers, or our teachers as parental figures. Those older than us have more knowledge, and so logically they should be the ones dispelling that knowledge to those lacking it. If you compare the two charts above, though, it’s clear that Super Metroid intends to subvert this understanding. The scientists who have custody over the Metroid larva are learning from it, studying its capabilities. The childlike Etecoons who Samus protects at the end of the game teach her one of the most important techniques in the series. The children educate the parents while the game educates the player.

Super Metroid not only has far more thematic substance than many games that came before it, it also uses its medium to tell a nuanced, non-linear story in a way that is integrated with the gameplay rather than told through cutscenes or blocks of text—something many games that came after it are unable to do. All of these qualities come together to make the argument that video games, the youngest of all the art forms, have something valuable to teach us.

Luke Arnott explores how the Metroid series teaches its players concepts in this really great essay.

Zebes, according to the semi-canon manga, was colonized by the Space Pirates after they orphaned Samus and killed all of the Chozo, an intelligent alien species who adopted her.

Not to keep bringing up the manga, however it provides an equally compelling interpretation. Both Mother Brain and Samus are the children of the Chozo, since it reveals that both were actually genetically engineered by this ancient bird race. In the manga, Mother Brain acts like a jealous sister, envying the attention the Chozo give to Samus. This isn’t relevant to Super, however it’s an interesting way to see things.